There are only two animal groups that can symbolically communicate where a specific location can be found: humans and honeybees. We all know how humans do it, through speech and sign language.

Honeybees do it through dance. Specifically, the waggle dance and the round dance.

Table of Contents

What Is the Waggle Dance?

The waggle dance is performed by a worker honeybee to tell fellow workers the precise location of a new food source, water source, or potential nesting site (Seeley, 2010). The waggle dance applies only to long distance locations; the round distance is done for short distances.

For young workers, this is typically their initiation into foraging. While other bees, such as bumblebees, tend to learn which flowers to go to by flying to each species individually (Heinrich, 1979), honeybees can use the dance as a first guide.

During foraging and later at the dance, the dancing bee emits four cuticular hydrocarbons, two of which specifically act as pheromones to entice the observers to head out and forage (Thom et al., 2007).

The Waggle Dance Performance

The dance is performed in a specific place, conveniently referred to as the “dance floor” and demarcated by chemical compounds (Tautz & Lindauer, 1997). In Apis mellifera, the dance is performed vertically, inside the nest cavity, in the dark, with observers following the dance by touching her with their antennae (Rohrseitz & Tautz, 1999). In other species with different nesting ecologies, the dance may be performed in the sun and include other signals (e.g., the raised abdomen of Apis florea; Dyer (1985)). Unless otherwise specified, this article will be centred around Apis mellifera, the common honeybee.

The dancer moves in one direction while waggling her body and vibrating her wings in a specific pattern. She will then turn back to the starting point to perform the run again, alternating between a clockwise and a counterclockwise turn.

See Seeley (1996) for a thorough breakdown.

Figure 2: The information in the waggle dance (Łopuch & Tofilski, 2020)

There are several components to it that provide different information:

- Direction is relayed by the angle of the waggling in relation to the direction of movement. This angle informs the workers that this is the direction they must fly in, in relation to the sun.

- Distance is relayed by the number of waggles the dancer performs per run and the time taken to do the run. It may also be that the wing vibrations are indicative of distance: the dancer emits a certain number of pulsed wing beats per run (Łopuch & Tofilski, 2017), and the number of pulses is correlated with target distance (Michelsen, 2003).

- Quality of the food is relayed by the total number of runs performed (George & Brockmann, 2019).

Other components, such as time taken for individual waggle, time taken for only the waggle section, or time taken for the turn back, may also provide information that we have not yet uncovered. For example, it has been suggested that vibrations produced during the dance may also have informational content, based on findings that dancers in open combs that better transmit vibrations recruit three times as many foragers as dancers in closed combs (Tautz, 1996).

The fact that the dance is performed several times implies that there is some error that creeps in every time since the dancing bee cannot follow the exact same direction and tempo (Couvillon et al., 2012). There is also variation between individual dancers describing the same route (Schürch et al., 2016), which can be followed down to varying gene expression levels (George et al., 2020). On average, the errors fall between 10 – 15º (de Marco et al., 2008).

The Cognitive Dimension of the Waggle Dance

The waggle dance is a behaviour that all foraging honeybees engage in, and the ability to encode and decode it is innate. The dance itself is dynamically generated depending on the precise environmental conditions. The distance to be conveyed is measured by the dancer calculating it through the total optic flow it has experienced in its trip (Dacke & Srinivasan, 2007). The dance is also enabled by some of the same neural systems that control learning and sensory processing, since disruptions during the pupal stage of a honeybee worker, for example abnormal temperature variations, affect an adult worker’s abilities to do the dance properly (Tautz et al., 2003), just as they affect learning and sensory processing abilities. Learning itself plays a critical role, as shown by moving bees between northern and southern hemisphere: adult bees moved to another hemisphere cannot decode the dance properly as the sun’s position is different, while their offspring learn where the Sun is and interpret dances correctly (Lindauer, 1961).

It is known for certain, from both experimental data and radar tracking of individual bees (Riley et al., 2005), that the waggle dance is a language that carries information for the receiver to decode, and that it is highly effective and standardised: bees who are danced to arrive at the conveyed location, where they are then guided by local environmental cues (visual and olfactory) to the precise flowers or nest sites they are supposed to examine.

Its existence is evidence of the relatively incredible intelligence that bees and insects can have. If you trap a bee in darkness several hours after it has followed a dance, it will still remember it and go to the correct location, correctly calculating the difference in the sun’s position between then and now (Lindauer, 1961). The dancer must have the capacity to calculate and remember that a certain food site has the potential to be interesting; it must remember its location and place it within the map it has constructed in its brain (Cheeseman et al., 2014); and then transmit this location to others. The followers, in turn, must be able to process and remember all the information specified by the dancer, and integrate it within their own memories.

After all, the waggle dance is not a direct order for the receiver worker bee to go to a place. It is merely a report and a suggestion, but many experiments have shown that experience plays a significant role in whether the potential recruit follows it: the memories triggered by the directional information described by the dance are more important than the precise directions given in the dance (Grüter & Farina, 2009). If a bee has already been to the location described, it will remember it and the details about it, and choose whether to go there, informed by its previous experience of the route to the site and worthiness of the site (Biesmeijer & Seeley, 2005). The dance is the primary source of information only when the site is a new one (Hasenjager et al., 2020).

In turn, this means that the dance language exposes a great degree of individuality and individual decision-making, with these decisions affecting the entire colony’s success (Camazine & Sneyd, 1991). Seeley et al. (1991) showed that foraging bees will respond to a dance’s indication of a richer food site, which is of critical importance if you consider the food landscape to be constantly changing in response to increased foraging, and disturbances from weather or other animals.

Foragers will also consult with each other and other nestmates to get an idea of predation risks (Nieh, 2010), which food sites are being exploited already, the amount of food available, and how much is being brought in, to make a decision on which foraging run to pursue in order to maximise the benefit for the colony by avoiding overcrowding and optimising food intake (Seeley & Towne, 2002).

How Did the Waggle Dance Evolve?

Recognition of direction relative to the sun’s azimuth and gravity is also widespread among all insects, including Hymenoptera (Jander, 1963). For example, cockroaches, beetles, and ants will always run at the same angle relative to the light source, no matter how tilted the surface is.

Specific movements related to a particular stimulus exist in many insects. Courtship dances are aplenty, and even dances related to food are not uncommon. For example, individuals of the blowfly Phormia regina will fly in circles around a sugar droplet, with the shape of the circle reflecting how tilted the surface is: a perfect circle means it is a level surface, while an oblate circle means a more tilted one (Dethier et al., 1965).

Specifically in bees, Melipona and Trigona stingless bees were found by Esch et al. (1965) to produce pulsed sounds, with the timing between pulses correlated to distance to a food source, a behaviour also found in honeybees. Trigona and honeybees also share another relevant behaviour of running and vibrating to wake up other members of the hive, so they pay attention.

Such behaviours could possibly be considered as pre-requisites for the evolution of the waggle dance in the honeybee, since all the components are already there: the navigational aspect; alerting co-workers to pass on a message; and computing and transmitting information on direction and distance. The dance merely adds extra layers of complexity and information to this basic model.

If we take the dance as a language, it has an established grammar and syntax in all honeybee species, and there has long been compelling evidence of species-specific dialects (Lindauer, 1956). Species-specific distinctiveness is present depending on nesting conditions, as already mentioned. For example, species with dancers who perform in dark (night-time or within the comb) produce auditory signals (Kirchner & Deller, 1993), while those that perform in daylight do not produce them (Kirchner et al., 1996).

There are also differences in how distance is translated, which evolve in consideration of the specific ecological conditions faced in their local habitats and foraging areas. For example, a larger foraging range will need more waggles per run, which may take too long to perform and get confusing, so that population will encode more distance within each waggle, at the cost of less precision (Dyer, 2002).

Further Research

The behavioural components of the dance are well-studied from both experimental and modelling perspectives, in main part due to the important relevance of honeybee foraging and pollination for agriculture (Calderone, 2012), and knowing where they are getting their nutrition from is important for maintaining domesticated bee health (Balfour & Ratnieks, 2017). Despite this, there are potentially several missing pieces of information about potentially overlooked factors that play a role in the dance (for example sound and vibrations).

Thankfully, advances in machine vision and automated multimedia processing are enabling more in-depth ways of analysing dances, which will lead to much more precise data, proper quantification of inter- and intra-individual differences, and possibly overlooked factors and correlations (e.g. Okubo et al. (2019)).

In the context of agricultural application, another interesting array of questions concerns comparative studies into dialects, especially with geographical hybrids and mixed colonies: which dialect is applied by the hybrids and are mixed colonies confused, and how do they evolve to adapt in new, more controlled industrial circumstances?

Where there is a real dearth in research is in examining the neural side of the dance, both for the dancer and for the forager. This essentially includes studying how the information is encoded and decoded in their brains, and how all the stimuli are separated, processed, and finally integrated together with memories and “peer pressure” to make a cohesive plan of action. While we know at least the molecular and neural fundamentals of how navigation is done, and how odours and vibrations are sensed and processed, all this knowledge needs to be brought together into a cohesive whole – and a naturalistic one, keeping in mind that the dance of many species takes place in a sensorially overloaded space.

History Of Research

The Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch was the first to propose that honeybee foragers told nestmates where to find food through dance in 1946 (von Frisch, 1946; see von Frisch (1967)). Despite earning him part of a Nobel Prize in 1973 and this rightly being hailed as one of the most exciting scientific discoveries of the 20th century (Couvillon, 2012), it wasn’t until Riley et al. (2005) that all doubts (see Gould (1975)) were conclusively expelled, and the waggle dance’s effect was empirically shown.

The initial scepticism was due, in part, to the lack of methodology for excluding a potential role of odour in guiding the recruited workers, and from differing philosophies as to the cognitive capabilities of animals (see Munz (2005)).

While the dance is now accepted as a language without any doubts, that early scepticism was not entirely unfounded: as mentioned in the Cognitive section, the dance may not be the primary source of information, and odour is also known to be an important guiding source: worker bees can be guided by the smell of nectar shared by the dancing forager through trophallaxis (Farina, 2000), or even just by scents she is carrying (Cholé et al., 2019). On the other hand, the hive is an exceedingly small and crowded space, and it is difficult for single odours to really be isolated by an individual bee.

References

- Balfour NJ & Ratnieks FLW. 2017. Using the waggle dance to determine the spatial ecology of honey bees during commercial crop pollination. Agricultural and Forest Entomology 19, 210 – 216.

- Biesmeijer JC & Seeley TD. 2005. The use of waggle dance information by honey bees throughout their foraging careers. Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology 59, 133–142.

- Calderone NW. 2012. Insect Pollinated Crops, Insect Pollinators and US Agriculture: Trend Analysis of Aggregate Data for the Period 1992–2009. PLoS ONE 7, e37235.

- Camazine S & Sneyd J. 1991. A model of collective nectar source selection by honey bees: Self-organization through simple rules. Journal of Theoretical Biology 149, 547 – 571.

- George EA & Brockmann A. 2019. Social modulation of individual differences in dance communication in honey bees. Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology 73, 41.

- George EA, Bröger A-K, Thamm M, Brockmann A & Scheiner R. 2020. Inter-individual variation in honey bee dance intensity correlates with expression of the foraging gene. Genes, Brain and Behavior 19, e12592.

- Cheeseman JF, Millar CD, Greggers U, Lehmann K, Pawley MDM, Gallistel CR, Warman GR & Menzel R. 2014. Way-finding in displaced clock-shifted bees proves bees use a cognitive map. PNAS 111, 8949 – 8954.

- Cholé H, Carcaud J, Mazeau H, Famié S, Arnold G & Sandoz J-C. 2019. Social Contact Acts as Appetitive Reinforcement and Supports Associative Learning in Honeybees. Current Biology 29, 1407 – 14113.e3.

- Couvillon MJ. 2012. The dance legacy of Karl von Frisch. Insectes Sociaux 59, 297 – 306.

- Couvillon MJ, Phillipps HLF, Schürch R & Ratnieks FLW. 2012. Working against gravity: horizontal honeybee waggle runs have greater angular scatter than vertical waggle runs. Biology Letters 8, 540 – 543.

- Dacke M & Srinivasan MV. 2007. Honeybee navigation: distance estimation in the third dimension. Journal of Experimental Biology 210, 845 – 853.

- Dethier VG, Solomon RL & Turner LH. 1965. Sensory input and central excitation and inhibition in the blowfly. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 60, 303–313.

- Dyer FC. 1985. Mechanisms of dance orientation in the Asian honey bee Apis florea L. Journal fo Comparative Physiology A 157, 183 – 198.

- Dyer FC. 2002. The Biology of the Dance Language. Annual Review of Entomology 47, 917 – 949.

- Esch H, Esch I & Kerr WE. 1965. Sound: An Element Common to Communication of Stingless Bees and to Dances of the Honey Bee. Science 149, 320 – 321.

- Farina W. 2000. The interplay between dancing and trophallactic behavior in the honey bee Apis mellifera. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 186, 239 – 245.

- von Frisch K. 1946. Die Tänze der Bienen. Springer Verlag, Berlin.

- von Frisch K. 1967. The Dance Language and Orientation of Bees. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

- Gould JL. 1975. Honey bee recruitment: the dance-language controversy. Science 189, 685 – 693.

- Grüter C & Farina WM. 2009. The honeybee waggle dance: can we follow the steps? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24, 242 – 247.

- Hasenjager MJ, Hoppitt W & Leadbeater E. 2020. Network-based diffusion analysis reveals context-specific dominance of dance communication in foraging honeybees. Nature Communications 11, 625.

- Heinrich B. 1979. “Majoring” and “Minoring” by Foraging Bumblebees, Bombus Vagans: An Experimental Analysis. Ecology 60, 245 – 255.

- Jander R. 1963. Insect Orientation. Annual Review of Entomology 8, 95 – 114.

- Kirchner WH & Dreller C. 1993. Acoustical signals in the dance language of the giant honeybee, Apis dorsata. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 33, 67 – 72.

- Kirchner WH, Dreller C, Grasser A & Baidya D. 1996. The silent dances of the Himalayan honeybee, Apis laboriosa. Apidologie 27, 331 – 339.

- Lindauer M. 1956. Über die Verständigung bei indischen Bienen. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Physiologie 38, 521 – 557.

- Lindauer M. 1961. Communication Among Social Bees. Harvard University Press, Harvard MA.

- Łopuch S & Tofilski A. 2017. Direct Visual Observation of Wing Movements during the Honey Bee Waggle Dance. Journal of Insect Behavior 30, 199 – 210.

- Łopuch S & Tofilski A. 2020. Impact of the quality of food sources on the wing beating of honey bee dancers. Apidologie (in press).

- de Marco RJ, Gurevitz JM & Menzel R. 2008. Variability in the encoding of spatial information by dancing bees. Journal of Experimental Biology 211, 1635 – 1644.

- Michelsen A. 2003. Signals and flexibility in the dance communication of honeybees. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 189, 165 – 174.

- Munz T. 2005. The Bee Battles: Karl von Frisch, Adrian Wenner and the Honey Bee Dance Language Controversy. Journal of the History of Biology 38, 535 – 570.

- Nieh JC. 2010. A Negative Feedback Signal That Is Triggered by Peril Curbs Honey Bee Recruitment. Current Biology 20, 310 – 315.

- Okubo S, Nikkeshi A, Tanaka CS, Kimura K, Yoshiyama M & Morimoto N. 2019. Forage area estimation in European honeybees (Apis mellifera) by automatic waggle decoding of videos using a generic camcorder in field apiaries. Apidologie 50, 243 – 252.

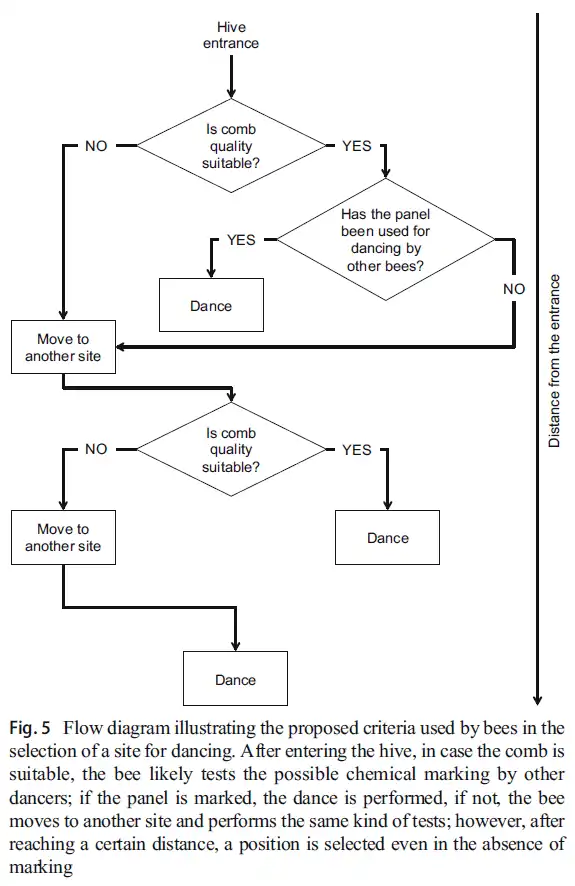

- Ortis G, Frizzera D, Seffin E, Annoscia D & Nazzi F. 2019. Honeybees use various criteria to select the site for performing the waggle dances on the comb. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 73, 58.

- Riley JR, Greggers U, Smith AD, Reynolds DR & Menzel R. 2005. The flight paths of honeybees recruited by the waggle dance. Nature 435, 205 – 207.

- Rohrseitz K & Tautz J. 1999. Honey bee dance communication: waggle run direction coded in antennal contacts? Journal of Comparative Physiology A 184, 463 – 470.

- Schürch R, Ratnieks FLW, Samuelson EEW & Couvillon MJ. 2016. Dancing to her own beat: honey bee foragers communicate via individually calibrated waggle dances. Journal of Experimental Biology 219, 1287 – 1289.

- Seeley TD. 1996. The Wisdom of the Hive. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

- Seeley TD. 2010. Honeybee Democracy. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ.

- Seeley TD, Camazine S & Sneyd J. 1991. Collective decision-making in honey bees: how colonies choose among nectar sources. Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology 28, 277 – 290.

- Seeley TD & Towne WF. 1992. Tactics of dance choice in honey bees: do foragers compare dances? Beavioral Ecology & Sociobiology 30, 59 – 69.

- Tautz J. 1996. Honeybee waggle dance: recruitment success depends on the dance floor. Journal of Experimental Biology 199, 1375 – 1381.

- Tautz J & Lindauer M. 1997. Honeybees establish specific sites on the comb for their waggle dances. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 180, 537 – 539.

- Tautz J, Maier S, Groh C, Rössler W & Brockmann A. 2003. Behavioral performance in adult honey bees is influenced by the temperature experienced during their pupal development. PNAS 100, 7343 – 7347.

- Thom C, Gilley DC, Hooper J & Esch HE. 2007. The Scent of the Waggle Dance. PLoS ONE 5, e228.

Leave a Reply